In his article, Dr. Vali Kaleji, a Tehran-based expert on Central Asia and Caucasian Studies, postulates that the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation that was held on October 17-18 in Beijing can significantly influence transportation and transit in Eurasia. On the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), this megaproject has been materially affected by the conflict in Ukraine and the Western sanctions against Russia. These circumstances can lead to the strengthening of the Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor in the BRI, which overlaps with the Middle Corridor or the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR). Indeed, given the growth of trade and transit between Russia and China, the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor (CMREC) road and rail routes can develop via the BRI. Indeed, Moscow hopes that the Arctic Blue Economic Corridor can be defined as an official part of the Maritime Silk Road. Eurasian countries can attract an important part of the financial resources of the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank and the Silk Road Fund. However, because it has been writing off loans, China should be expected to be much more conservative and cautious in lending and investing during the second decade of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation was held between October 17 and 18 in Beijing, China. It marked the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). “The BRI is a massive infrastructure and economic development project initiated by the Chinese government in 2013. It was announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping during his visit to Kazakhstan in September 2013.” On the 10th anniversary of this megaproject, delegations from 140 countries, notably from Latin America and Africa and more than 30 international organisations, participated in the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing; the number of registered participants exceeded 4,000 people. At this forum, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced eight major steps China will take to support high-quality Belt and Road cooperation.

While the Maritime Silk Road aims to construct new ports or enhance existing ones along the sea routes connecting China’s coastline, the objective of the Silk Road Economic Belt is to enhance China’s land-based transportation connections to Europe and Asia through six major corridors within the BRI. These include the Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor, the China – Central Asia – West Asia Corridor, the China – Mongolia – Russia Corridor, the China – Pakistan Economic Corridor, the China –Myanmar – Bangladesh–India Corridor, and the China – Indochina Peninsula Corridor. Therefore, among the six main land routes, three pass through different regions of Eurasia, clearly indicating the role and place of Eurasia in this transit and transportation megaproject. As a result, an important question arises: what were the results of the Belt and Road Initiative Summit for transport connectivity in Eurasia? In answering this question, the following key points are important.

First, the conflict in Ukraine, extensive Western sanctions against Russia and transit restrictions splitting Russia from the eastern European Union have had a direct and negative impact on the Northern Corridor of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Indeed, the New Eurasian Land Bridge project linking Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Belarus to East Asia has been curtailed. Under this circumstances, the Middle Corridor and the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), which starts from Southeast Asia and China, and then runs through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia and then stretches to European countries, are increasingly seen as potential alternatives to trade routes which rely on Russia.

For this reason, in March 2022, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkiye and Kazakhstan produced a quadrilateral statement on the need to develop the Trans-Caspian International Transport Corridor or Middle Corridor. In this regard, they have significantly increased transit and logistics relations with China. In particular, China and Georgia upgraded their bilateral ties to a strategic partnership on July 31, 2023 and the two sides have agreed to strengthen coordination and collaboration on China’s global projects such as the Belt and Road and Global Security initiatives. Therefore, the first important result of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation will be the strengthening of the Middle Corridor in the BRI as part of The Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor, which stretches along its main corridor from Xinjiang Province in Western China, through Kazakhstan, across to Azerbaijan, Georgia and onto Turkey and the European Union. The Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor is depicted in the map below.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the first step of the eight steps proposed by President Xi Jinping at the 3rd Belt and Road Forum was referring to China's future programs along this route as a great example of “combined and multidimensional transport” in the BRI. In this regard, he mentioned “building a multidimensional Belt and Road connectivity network” and said:

Although the response to the conflict in Ukraine, anti-Russian sanctions and the blocking of Russian routes to Eastern Europe are undeniable, China also has many trade disputes with the West which can have a negative effect on the performance and quality of this important part of the BRI. At the 3rd Belt and Road Forum, the absence of European leaders was quite noticeable. While the leaders of the Czech Republic, Greece and Italy had attended the two previous Belt and Road Forums, they did not participate in the most recent one and Viktor Orbán was the only leader of an EU member state who participated in the event. Some analysts believe that it is the result of President Putin's presence at this meeting and China's alleged support for Russia in the conflict in Ukraine. However, it seems that the level of differences now extends beyond this. Italy, the only member of the Group of 7 nations to sign on to the scheme, is now looking for a way out. There is no doubt that this process will be an important challenge for Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey, which play the role of a bridge between two important economic poles of the world, China and the European Union, in the Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor and Middle Corridor.

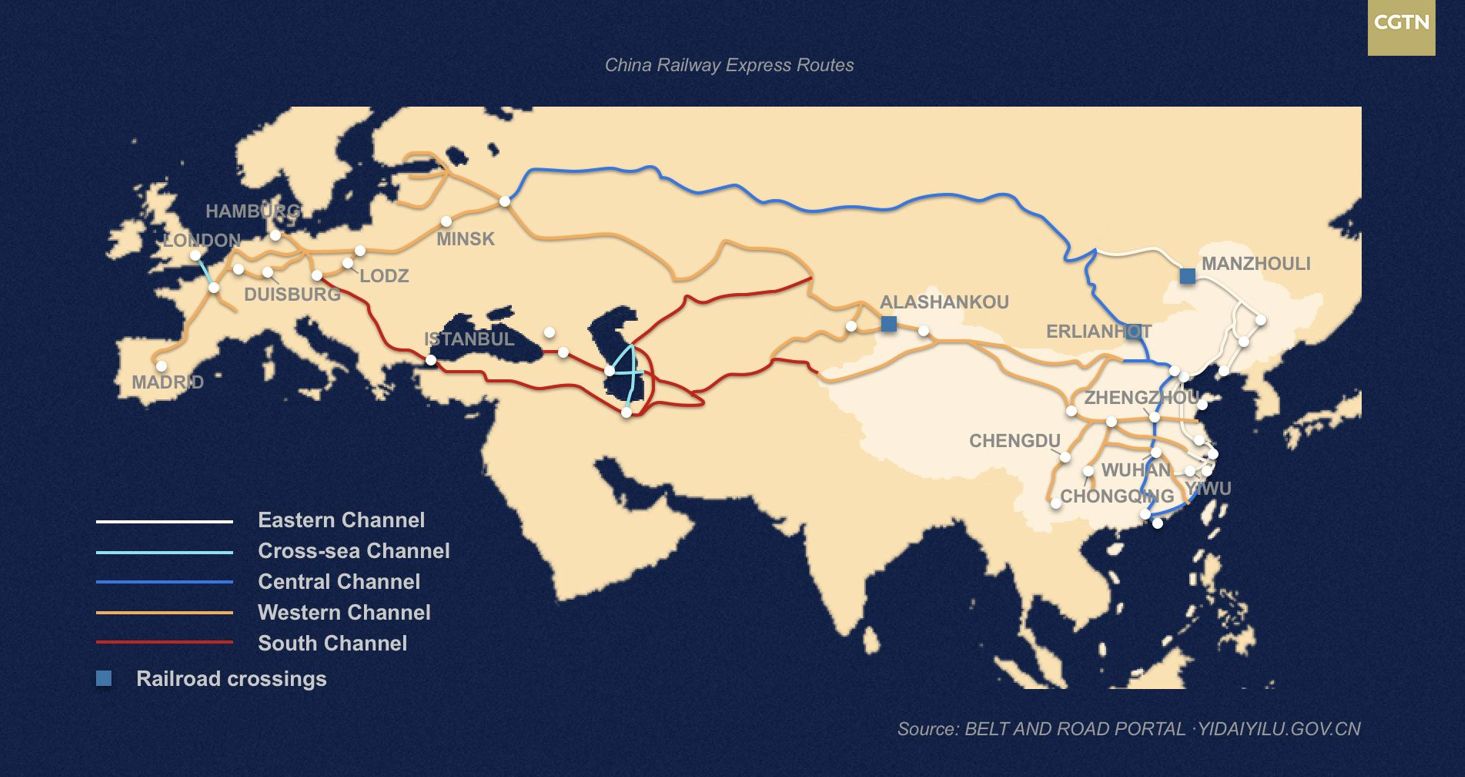

Indeed, the negative impacts of the conflict in Ukraine stand in the way of Beijing's ambitions to make a China-Europe Railway Express an important part of the BRI. As shown in the map below, the central channel (dark blue) and western channel (light brown) of the China-Europe Railway Express pass via the Russian Railways network, which connects the densely populated eastern regions of China to Europe. In fact, “the infrastructure strategy aims to promote freight trains running from China, across Russia and then through Ukraine or Belarus on to the European Union. However, in the wake of the conflict in Ukraine, Russian Railways are under EU and US financial sanctions, and it's tricky to insure products being transported through Russia because of the war and sanctions.” Under these circumstances, the railway route in the Middle Corridor or south channel (dark brown) is a rail alternative linking China to Europe that bypasses Russia. However, this route features “combined transportation”; cargo and goods are transported from the ports of Aktau in Kazakhstan and Turkmenbashi in Turkmenistan by ship via the Caspian Sea to the port of Baku. From there, they are transported to Georgia and Turkey via the Baku rail route, which increases the time and cost of transit. Another part of the “south channel” (dark brown) crosses through Iran, connecting China and Central Asia to Turkey and the European countries. The first direct train from China arrived in Iran in February 2016. The routes of the China-Europe Railway Express are depicted on the following map.

“The Eurasian Land Bridge Corridor” which overlaps with “the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) or “the Middle Corridor” (source: openstreetmap.org)

The Routes of China-Europe Railway Express (source: CGTN)

The second result of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum will be the strengthening of land and rail routes between China and Russia. Although China's transit and trade route to Europe is blocked from Russia amid the conflict in Ukraine, the volume of bilateral trade and transit between Russia and China has increased significantly. Bilateral trade turnover reached a record high of 190 billion USD in 2022 (29 percent higher year-on-year), and $94 billion in the first five months of 2023 (41 percent higher year-on-year). In 2023 bilateral trade is likely to total about US$235 billion. It is clear that this growing volume of trade requires the development of transit routes and transportation infrastructure. It can benefit the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor (CMREC) which is one of the six major corridors envisioned by the Belt and Road Initiative which coincides with the interests and goals of Moscow in Russia’s Pivot to Asia, especially trade with China and the development of Russia’s Far East. “In total, over the past decade, 7.2 trillion rubles (US$1 trillion) has been invested in Russian Far East projects, while last year, over 140 new enterprises began operating in the region. As it borders China, foreign investment in Russia’s Far East increased 23% in 2022.”

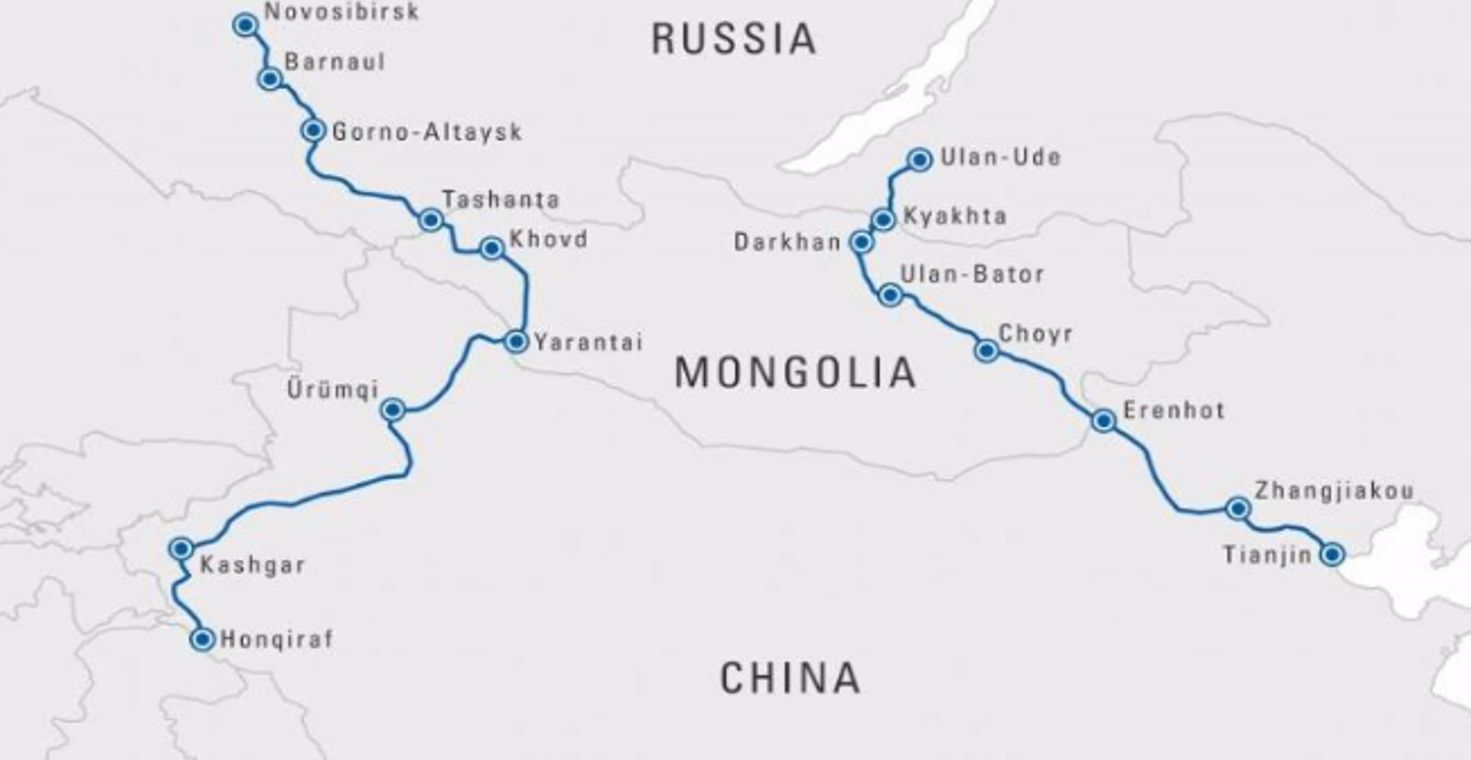

Therefore, one of the possible results of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation will be the strengthening of China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor (CMREC) in the process of developing transit and trade relations between China and Russia. This process will include both CMREC road and rail routes. The road routes include Asian Highway Route No. 3 from Ulan-Ude, Russia to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia to Beijing to Tianjin port (China), and Asian Highway Route No. 4 from Novosibirsk, Russia to Urumqi, China to Kashgar, to Honqiraf (on China’s border with Pakistan). However, “road transit via Mongolia awaits a full-fledged launch. The obstacles are many, including the level of road infrastructure development, difficulties in building logistics chains, and the limited capacity of border checkpoints. The AN-3 section of the highway between Darkhan and Ulan Bator is undergoing a protracted overhaul, with full commissioning not expected until late 2023.” The road routes of the CMREC are depicted on the map below.

The road routes of “China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor” (CMREC) in the Belt and Road Initiative (source: Modern Diplomacy)

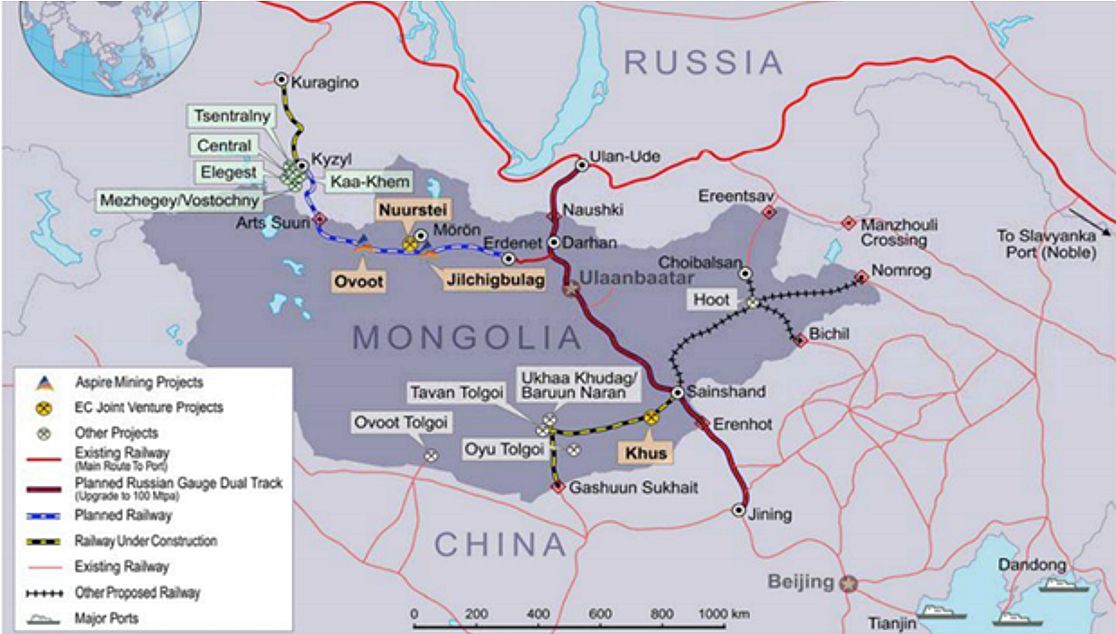

Indeed, “while modernization of the Central Railway of CEMREC (Ulan-Ude — Naushki — Ulan-Bator — Erlian — Beijing — Tianjin) still requires a feasibility study, the expediency of building rail corridors in the Eastern (Borzya — Solovyevsk — Choibalsan — Huut — Bichigt — Zuun-Khatavch — Chifeng — Chaoyang — Jinzhou/Panjin) and Western (Kuragino — Kyzyl — Tsagan-Tolgoi — Kobdo — Takeshken — Hami-Urumchi area) flanks is a matter of debate”. In this regard, a tripartite consensus among Russia, Mongolia and China has been reached to upgrade the Tianjin-Ulaanbaatar-UlanUde Central Route into a double-track electrified railway line by 2030. The rail routes of CMREC are depicted on the map below.

The Rail Routes of “China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor” (CMREC) in the Belt and Road Initiative (source: Indian Council of World Affairs)

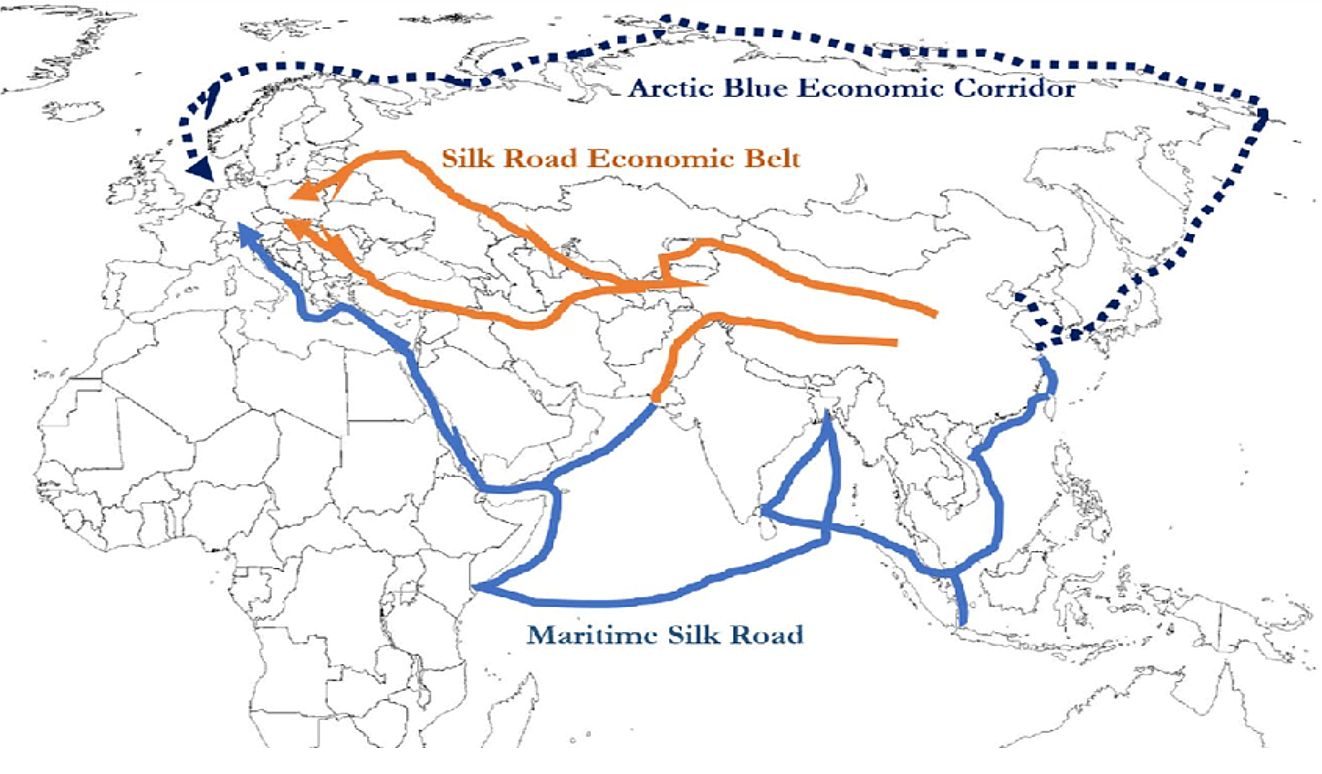

On the other hand, the beginning of Russia’s military operation in Ukraine consolidated Russia’s “pivot to the East” in the Arctic. The interaction between Russia and China on the development of the Arctic region is becoming one of the important areas of Russian–Chinese “comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation for a new era”. Under such circumstances, the “Arctic Blue Economic Corridor” is a new route for trade and transit from China to the northwestern parts of Russia and also northern Europe which bypasses Russian land and railways routes. President Vladimir Putin confirmed the northern routes at the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing. He said:

As for the Northern Sea Route, Russia does not just offer its partners [the opportunity] to actively use its transit potential, I will say more: we invite interested states to participate directly in its development, and we are ready to provide reliable icebreaker navigation, communication and supplies. Starting next year, navigation for ice-class cargo ships along the entire length of the Northern Sea Route will become year-round.”

It is clear that turning the “Arctic Blue Economic Corridor” into an official part of the Maritime Silk Road is a time-consuming process that requires study and the examination of technical issues, as well as a calculation of the costs an benefits of ships passing through the harsh conditions of the southern regions of the North Pole. The Arctic Blue Economic Corridor route is depicted on the map below.

The Route of “Arctic Blue Economic Corridor” which can be an official part of the Maritime Silk Road (source: China’s Arctic Engagement)

The third result of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation will be China's investment in infrastructure and new transport and transit technology in Eurasia. Chinese President Xi Jinping mentioned at the forum that “the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China will each set up a RMB 350 billion financing window. An additional RMB 80 billion will be injected into the Silk Road Fund”. Indeed, he predicts that “in the next five years (2024-2028), China’s total trade in goods and services is expected to exceed USD 32 trillion and USD 5 trillion respectively.” Based on the eight steps that he proposed, it can be expected that a part of this huge investment in Eurasia will be spent in areas such as the “establishment of pilot zones for Silk Road e-commerce cooperation”, “advancing high standards in opening up cross-border service trade and investment”, “promote both signature projects and ‘small yet smart’ livelihood programs” and “deepen cooperation in areas such as green infrastructure, green energy and green transportation.” In this process, the Eurasian countries can be part of “the BRI International Green Development Coalition” and use China's investment and credit in a targeted manner by designing and defining projects in the aforementioned areas.

However, there is no doubt that in the second decade of the Belt and Road Initiative, China will be much more conservative and cautious in offering loans and investing. Many experts believe that in the first ten years of the Belt and Road Initiative, China did not accurately evaluate the efficiency or effectiveness of investment in infrastructure projects in many countries such as Mongolia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Zimbabwe. Between 2020 and March 2023, China renegotiated and/or wrote off loans worth US$78.5 billion – money otherwise invested in signature projects such as roads, railways, ports, airports, etc. China has also sharply cut the pace of funding for BRI projects, especially as the Covid-19 crisis has bit into global economic growth. “This policy of renegotiation and/or writing off loans comes in addition to the newish policy of doling out so-called ‘rescue loans’ to help the BRI recipients avoid sovereign default.” Therefore, it seems that China will tread more cautiously in investing and lending to Mongolia and the Central Asian countries in this decade of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Finally, China's major challenge in advancing the Belt and Road Initiative in Eurasia will be coordinating and combining the goals and interests of this initiative with The International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and also the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS. Although President Xi Jinping did not mention any of the mentioned issues in his speech at the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, the similar or conflicting interests and goals of the North-South Corridor and the aforementioned organizations can affect the quantitative and qualitative development of the Belt and Road Initiative in its second decade.