The Caribbean island country has been living under a US embargo since the early 1960s. With scarce natural resources, but a lot of creativity, the country not only managed to face economic isolation, but also developed some top-tier specialisations, writes Valdai Club expert Emanuel Pietrobon.

The West-sponsored Ukraine-related sanctions-regime has converted Russia into the most-sanctioned country in world history. With a little less than 15,000 sanctions against its individuals, entities and institutions, Russia ranks first in the global ranking of sanctions-hit countries, with Iran far behind in second place — with about 4,000 sanctions.

To understand the uniqueness of the Ukraine crisis-related sanctions-regime, all that is needed is a comparison: as of March 2023, Russia was dealing with almost 15,000 sanctions, while the world’s seven most sanctioned economies totalled approximately 11,500 sanctions.

The world is observing Russia’s reaction to this unprecedented economic warfare. The United States does want to show that the era of dollar supremacy is not over yet. China is taking notes from both contenders — how the West fights economic wars, and how to react to global embargoes. The emerging powers of the Global South watch and ponder — to dedollarise or not to dedollarise, that is the question.

The Russia-related sanctions-regime has been designed in such a way as to inhibit the country’s growth and development in the long-term by depriving it of revenues and know-how, with Ukraine playing a fundamental role in this scheme: the battlefield of attrition warfare combining the elements and aims of the Soviet-era Afghan insurgency and the Iran-Iraq war.

Posterity will judge who is right and who is wrong. The West — whose economic warfare could eventually lead Russia to collapse, with China standing alone in its struggle for the multipolar transition. Russia — whose resistance economy could serve as a lodestar for autarky-seeking and/or sanctions-hit countries.

Russia and likeminded countries have a lot to learn in their quest for greater economic autonomy from the successes and failures of players from every era. It can learn from very similar yet different historical episodes of economic warfare, such as the British response to Napoleon’s Continental Blockade and the Chilean reaction to the US-backed Invisible embargo. Now is the time to draw lessons from the country that survived the world’s longest embargo: Cuba.

El bloqueo – An overview

The origins of the world’s lengthiest embargo date back to the early 1960s. The country’s post-Batista ruling elite was composed of fiercely anti-American forces, but their decision to ally with the Soviet Union and to embrace Communism would only come after the events of 1961 and 1962, respectively the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Missile Crisis.

In 1962, the already existing economic pressures would become what William LeoGrande has dubbed “the most comprehensive US economic sanctions regime against any country in the world,” which is popularly known as ‘el bloqueo’, consisting of measures that punish almost any type of trade with and investment in Cuba, with limited forms of development cooperation and humanitarian aid accepted. Besides trade and investments, the embargo provides restrictions on remittances, it prohibits access to a wide range of American-made software and information technologies, and it denies access to drugs, vaccines and healthcare tech made with US licences and patents. Against the background of formal sanctions, the United States is known to put pressure on anyone who wants to trade with and invest in Cuba, even in non-sanctioned sectors.

The impact of the embargo, at the time of the proclamation, was tremendous: Cuba was heavily dependent on commercial exchanges with the US, to which it exported up to 80-85% of what it produced and from which it imported 60-70% of what it consumed.

Overall, the sanctions-regime is estimated to have damaged the Cuban economy by $750-975 billion over a sixty-year period (1960-2020), playing a decisive role in the underdevelopment of the country.

While the damage has been enormous, the embargo never achieved the political goal of bringing about regime change. Conversely, the Cuban Communist Party’s economists managed to build a partly sanctions-proof economic system, undoubtedly resistant and resilient, capable of ensuring acceptable living standards for many and of achieving a series of world-recognised records.

Inefficiency is a disease – and it requires the right pills

Cuba was able to adapt quickly to the new trade environment. By 1962, Cuba had imported nearly 80% of its needs from the Second World, exporting almost all of its national production to it. The United States reacted to the speedy diversification by convincing the Organisation of American States to join the embargo, effectively cutting the island off from the Americas. By 1968, Cuba-LatAm import-export was worth $1 million, down from $84 million ten years earlier. Similarly, the United States managed to lower Cuba-Western Europe trade by weaponising the right to offer refuelling and harbouring for ships and by fining heavily its non-compliant partners — a surviving practice, as shown by the nearly two billion dollar fine paid by Commerzbank in 2017.

Cuba’s reaction to the bloqueo’s enlargement was essentially based on the militarisation of the economy; that is, many sectors were entrusted to the armed forces, and on the adoption of a dirigiste model of economic management. It did not work: production targets were rarely achieved. It still doesn’t work: production targets are rarely fully achieved, and shortages are frequent. Inefficiency is Cuba’s second plague. In any case, the Cuban model wasn’t and isn’t a fiasco at all.

Shortly after the outbreak of economic warfare, Cuba found itself brain-poor because the United States had convinced thousands of highly skilled workers to leave the island in pursuit of better paid jobs — the same strategy would later be used against Allende’s Chile. In 1961, Cuba only had 3,000 physicians, down from 6,000 two years earlier. The government addressed the situation by launching a nationwide call for aspiring experts and by asking for economic consulting from CEPAL and from the Soviet-led bloc. The ensemble of suggestions would take the form of the so-called budgetary system, a model of economic management based on the employment of forefront accounting techniques, mathematical forecasting, and best practices, with the State seen and treated as a giant enterprise.

The budgetary system deprived enterprises of both financial independence and production planning autonomy, with the central government setting and funding the production targets for them. Managers had to update the Ministry of Industry on their firm’s progress through bi-monthly or quarterly updates, and they could get awards or face penalties depending on whether the objectives were achieved or not. Behavioural economics were used to fight inefficiency.

Results were mixed. In 1963, after a two-year experiment, Cuba had successfully diversified its import-export, but the scientific organisation had added extra weight to the already cumbersome bureaucracy, with a negative impact on production. There were too many goals, and too few resources. The only relevant achievements of the 1961-63 experiment would be the successful trade partner diversification and the lightning fast construction of a food factory.

The second experiment in the context of the budgetary system took place between 1964 and 1970, with the government setting the building of national heavy industry and agri-business diversification as top priorities. A two-year battle of production aimed at producing 10 million tons of sugar would end very close to achieving the target, with 8 million tons produced. By the end of the 1960s, the government had finalised the nationalisation campaign, sped up land distribution, and took the first steps towards the healthcare miracle and universal literacy. The success was due to de-emphasising centralised planning and bureaucratisation, which were both resized in favour of greater autonomy.

The second experiment had shown the authorities that the budgetary system had had its day. It helped the national economy face the early years of bloqueo by fostering work discipline and by increasing the SMEs’ economic resistance, but its ability to allocate resources efficiently declined as the economy grew more complex. The application of mathematical forecasting would have helped, but the backwardness of the means available left this intention on paper.

In any case, as written earlier, inefficiency would continue to affect Cuba’s economic performance in the decades to come. This was and is due to the fact that de-centralisation never led to full de-bureaucratisation and to full self-management, as the government kept setting targets, priorities, and funds. This issue persists.

Diversification is nothing without self-sufficiency

Cuba was heavily reliant on the United States, which was the main source of investments in the Cuban economy and, unquestionably, its primary trading partner. The bloqueo changed everything, shifting events in favour of the USSR.

Cuba’s lack of money was no problem for its new partners, who rediscovered the ancient but evergreen practice of bartering. Cuba used to exchange its most important products, like sugar and nickel, for fuel, equipment and technology. By the end of 1960, 80% of Cuba’s sugar exports went to the Communist-speaking countries of the Second World. Two years later, as a result of the Missile Crisis and the Bay of Pigs Invasion, Cuba-Second World relations were expanded to tourism, professional training, humanitarian cooperation, and so on.

While the Soviet-led could not help much with mass tourism — arrivals never exceeded 30,000 annually, far below the 300,000-500,000 from the US in the 1950s, it did help to achieve full diversification. By the mid-1980s, Cuba had so many Soviet-made tech and fuel that it began reselling the surplus to neighbouring countries.

Cuba’s mistake was that it didn’t use the cash inflows wisely. The Soviet Union alone granted it $300 million annually during the 1960s, which became $600 million a year in the following decade. Havana preferred to invest the sum in export-oriented industrialisation rather than in import substitution. As a result, despite aid, favourable trade terms and diversification, Cuba made no considerable progress toward even partial self-sufficiency, and kept remaining heavily reliant on foreign commodities.

In short, Cuba’s mistake was that it replaced one dependency with another — and diversification is nothing without self-sufficiency.

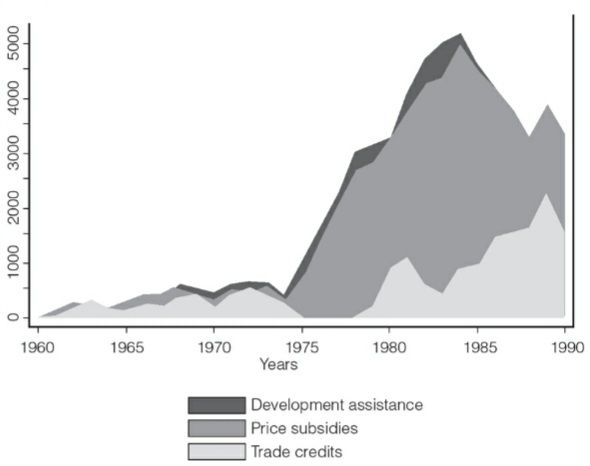

Soviet Union’sexpenditures on Cuba (million dollars) in the period 1960-90

Cuba’s second mistake was that it didn’t see the change coming, although it was a kind of elephant in the room. The Soviet Union began to reduce development assistance on the eve of 1985, price subsidies started recording a decrease in the same period, and economic aid was cut by 45% between 1989 and 1990.

Cuba could have mitigated the impact of the terrible post-Cold War economic crisis if only it had invested in import substitution and if, foreseeing the collapse of the Soviet-led bloc, it had begun to reorient import-export towards the Third World. When its old allies were consigned to history, Cuba experienced the worst economic crisis of its history, dubbed the “Special Period in Time of Peace” by Fidel Castro.

The Special Period in Time of Peace saw the island’s agricultural output fall by 54%, exports decrease 75%, real wages fall 25%, and its GDP contract by 36%. The government, driven by the goal of avoiding a famine-led regime change, launched a partial liberalization of the economy. However, the emergency recipe was doomed to fail.

Resistance is adaptation, but adaptation is...

When the Cold War ended, Cuba suddenly found itself isolated and the US tried to leverage on the situation with new sanctions. The government eventually managed to escape from the dead-end by re-thinking some of its economic dogmas. It worked, at least initially.

Cuba adapted quickly to the new environment. Too quickly, perhaps. The government said yes to foreign direct investments, it recognised self-employment, it established a foreign exchange market, it invested in the tourism industry, and it greenlighted comprehensive reforms targeting the entrepreneurial reality. The ensemble of actions would prove extremely and unpredictably harmful: the financial reforms led to mass speculation, the uncontrolled flows of tourists drove price increases, the higher amount of foreign currencies in circulation fuelled corruption. It took years to curb the economy’s dollarisation, to reassert control over private business and financial market and to contrast the growing bribery culture.

The lesson here is that while it is true that can be no resistance without adaptation, the latter must not be hasty. Decision makers must act with foresight and adopt a chess player mentality, that is, they always must think about what comes next.

Finally, if Cuba had learnt from the past, it would not have repeated the same mistake of not maximising the diversification momentum. In fact, the country proved unable to capitalize on the strategic partnership signed with new countries, specifically China and Venezuela, during the early 2000s. Cuba imported tech and equipment from China, oil from Venezuela, it exported nickel and other goods to both, and it received aid from both, but it did not invest the revenues in self-sufficiency development. Cuban authorities started speaking of import substitution when it was too late. Again. Indeed, when Miguel Diaz-Canel came out with proposals of import substitution industrialisation, Venezuela and China had already stopped their generously priced exports.

In any case, there’s something to learn from this period. One of the most interesting facts of Cuba-Venezuela cooperation during the Chavez era is an agreement, dated 2000, according to which Venezuela was to export 53,000 oil barrels per day at competitive prices in exchange for 20,000-30,000 Cuban doctors and educators. It was a landmark good-for-service agreement which has a lot to teach and endless possibilities for replication.

The urban agriculture experiment

Cuba’s resistance economy has lessons to teach to outside observers. After talking about what a resistance economy should not be — heavily centralised, excessively bureaucratised, reliant on foreign trade, poorly self-sufficient —, it’s time to talk about Cuba’s successes.

Forced to face a near-total lack of equipment and fuels in the post-Cold War era, which was about to provoke a countrywide famine, Cuba held a brainstorming to address the issue of food security. The country used to import fuel, fertilisers, spare parts and other agriculture-related tech from the Soviet-led bloc, but now it could no longer count on those countries.

As the saying goes, hunger sharpens ingenuity, and Cuba was literally hungry. Decision-makers found the solution to their problems in a pioneering experiment of urban agriculture which led to the construction of small-scale, semi-public open-air farms in a number of cities, including Havana, against the background of the proliferation of R&D centres on biofertilisers, pesticides, and seeds.

By 2003, Cuba had 35,000 acres of urban farms producing 3.4 million tons of food, employing 200,000 people and capable of reducing the consumption of fuels, chemical fertilisers and synthetic pesticides, respectively, by 50%, 10%, and 5% compared to ten years earlier. By 2012, Havana alone had more than 100,000 acres of urban farms.

Today, over 300,000 urban farms and food gardens operate in Cuba, where they are spread over more than one million hectares. Urban farms and food gardens are able to satisfy more than 50% of the domestic demand for fresh fruit and vegetables, with peaks of 90% in Havana. What is more, about one hundred university-linked scientific centres support the urban agriculture experiment with their research on soil exploitation, soil erosion, and biofertilisers.

The healthcare miracle

Healthcare hasn’t been spared by the bloqueo, something that has made it an existential threat to Cuba, given that America’s Big Pharma controls about 80% of the world market of pharmaceutical and medical patents. In practical terms, Cuba cannot buy a wide range of medicines and/or specialised equipment, from surgical microscopes to cancer-treating drugs, and those who violate the embargo face heavy fines, even when acting under mandate from humanitarian organizations — see the Chiron Corporation case.

Cuba had no choice but to invest in what we can call “healthcare sovereignty,” a term that the world has come to know with the outbreak of the COVID19 pandemic. The non-stop campaign of investment in healthcare sovereignty led to stunning results, which appear even more extraordinary if compared to the United States:

-

Cuba’s life expectancy at birth was 62 years in 1959, but has risen steadily since then, catching up with the US in 2020 and surpassing it in 2021 — 78.9 years against 76.1.

-

Cuba’s child mortality rate was 47.3 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1969 and it has declined to 4.1 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2022. In the US, deaths per 1,000 live births decreased from 21.4 to 5.5 over the same period.

-

Cuba has 8.2 physicians per 1,000 people; the US has 2.5 physicians per 1,000 people.

The comparison between Cuba’s improving healthcare and the US’ declining healthcare is the best way to make readers understand the importance of this case study: Cuba provides proof of what resource-poor but brain-rich countries can do.

Universities are also free for all citizens, with the State covering tuition fees and the cost of study materials. What is more, universities use to resort to calls for enrolment destined to meet specific national needs. For instance, universities mainly looked for potential technicians during the 1960s, but they have been looking for would-be doctors since the 1990s.

Universities are especially keen on obtaining medical students due to the fact that Cuba has managed to build an entire economy on the export of medical personnel over the years. Why Cubans seem so passionate about medicine can also have cultural explanations: Ernesto Guevara, one of the nation’s founding fathers, was a physician and continues to exert a powerful influence on the youth.

The demand for Cuban doctors is so high, as they have an excellent reputation and are cheap; even developed countries have begun to require their expertise, as Italy did during the COVID19 pandemic.

The numbers of this economy within an economy speak loud: 37,000 doctors “are exported” on average annually, with more than 70 countries benefitting from their expertise and with about $8 billion possibly earned by Cuba annually.

Cuban doctors are known for being inventive as well as used to getting big results with little resources, even when it comes to cancer and HIV/AIDS. Their fact-based reputation is inherently tied to the embargo, which obliges them to be creative, to treat diseases amid harsh conditions, to develop domestic versions of foreign drugs, and to design low-cost copies of foreign technology and equipment. As a result, in addition to exporting doctors, Cuba also sells low-cost medicine and medical technology to developing countries.

Conclusions

Cuba is a vivid example of economic resistance. No country has ever experienced such extensive and long-lasting economic warfare. Its case is made all the more unique by the fact that Cuba has no significant natural resources and it is also in an unfavourable geographical position, two factors that differentiate it from Iran, Russia and North Korea.

Cuban decision-makers have sometimes been short-sighted and other times far-sighted. They haven’t been able to tackle inefficiency or start import substitution programs, but they did achieve remarkable results in food security and healthcare.

Overall, what’ve learned from this case study is that economic resistance has a lot to do with non-economic factors:

-

Sanctions and resource scarcity can be overcome in the presence of ingenuity — it’s the Cuban doctors who claim that the healthcare miracle is the result of great creative efforts.

-

Ideology is a double-edged sword — it coalesced the population around the Communist regime, but prevented the typical inefficiencies of planned and centralized economies from being tackled.

-

There can be no economic resistance without moral integrity. The Cuban system gives great importance to moral incentives. Workers and managers attend compulsory courses designed to instil non-materialistic values, to promote work discipline, and to encourage goal-oriented behaviour. As a result, enterprises have a strong sense of social responsibility and give their all when the government launches battles of production.

-

No dollars, don’t worry. One of the greatest limits of the de-dedollarisation process is that the dollar is simply the dollar, so that foreign reserves composed of other currencies would risk remaining unused — this is why India struggles to sponsor the internationalization of the rupee, as countries wonder how and where they might use it. Cuba demonstrates that there is no need to trade in national currencies: there is barter, a very underrated practice that can allow countries to make goods-for-goods and even goods-for-services deals.

-

Carpe diem. It is essential that policy-makers take nothing for granted and that they make the most of it when the opportunity arises. Cuba has had multiple opportunities to fund a multi-sectoral self-sufficiency campaign, but has always spent the bulk of the revenues pursuing the wrong projects. Thinking that the order of things was destined to last, Cuba spent instead of investing and today finds itself in the limbo of chronic semi-development. No order lasts forever, the unexpected is always around the corner, this is why states must adopt a chess player mentality and thrifty behaviour.