Even if India’s lockdown is lifted to a certain extent, the disruption in important regional and economic pockets will continue. This is quite indicative for the COVID-19 economic impact on India in coming months. Under these circumstances a small positive growth rate in GDP, as suggested by the IMF, looks extremely improbable, writes Abhijit Mukhopadhyay, Senior Fellow with ORF’s Economy and Growth Programme. The article is published as part of the Valdai Club’s Think Tank project, continuing the collaboration between Valdai and Observer Research Foundation (New Delhi).

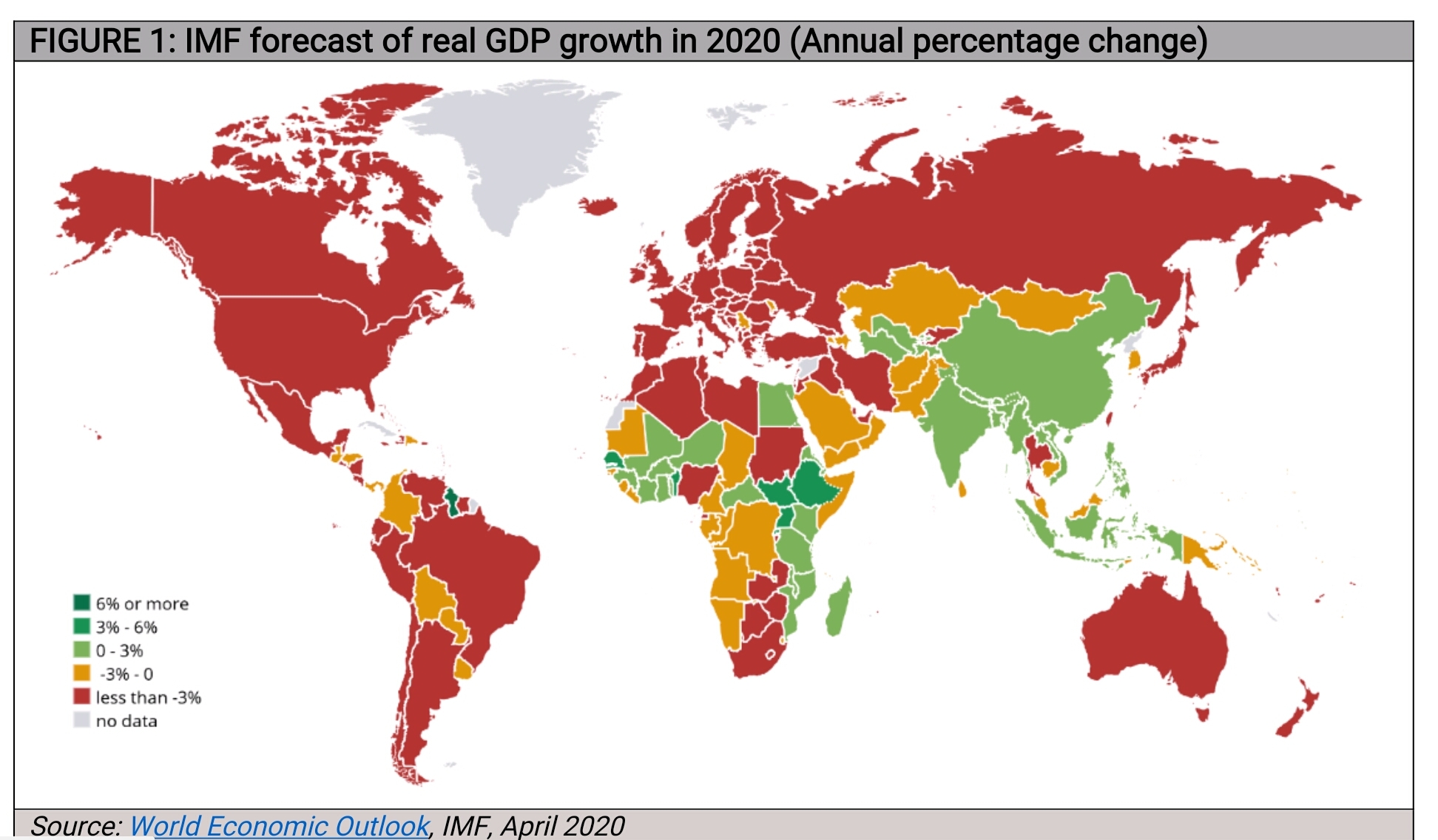

As the entire world is facing widespread lockdowns and economic disruptions due to the spread of COVID-19, IMF (International Monetary Fund) predicted that world output is to shrink by 3.0% in 2020 in April (World Economic Outlook). Advanced economies are estimated to contract by a whopping 6.1%. Output in the emerging markets and developing economies is also estimated to go down, but by a relatively less 1.0% (Figure 1).

Emerging and developing Asia, according to IMF, is likely to grow by a modest 1% – principally driven by a 1.2% Chinese and 1.9% Indian growth in GDP (gross domestic product). IMF projections have a general acceptance worldwide. Once these projections were out, cautious but relatively high hopes started building around future Indian economic prospect. Indian manufacturing taking off at the expense of China and similar discussions have since been initiated widely.

Will India (and China) be able to resist the worldwide economic ruin after the pandemic subsides? Is the anticipation of such a quick rebound based on credible facts?

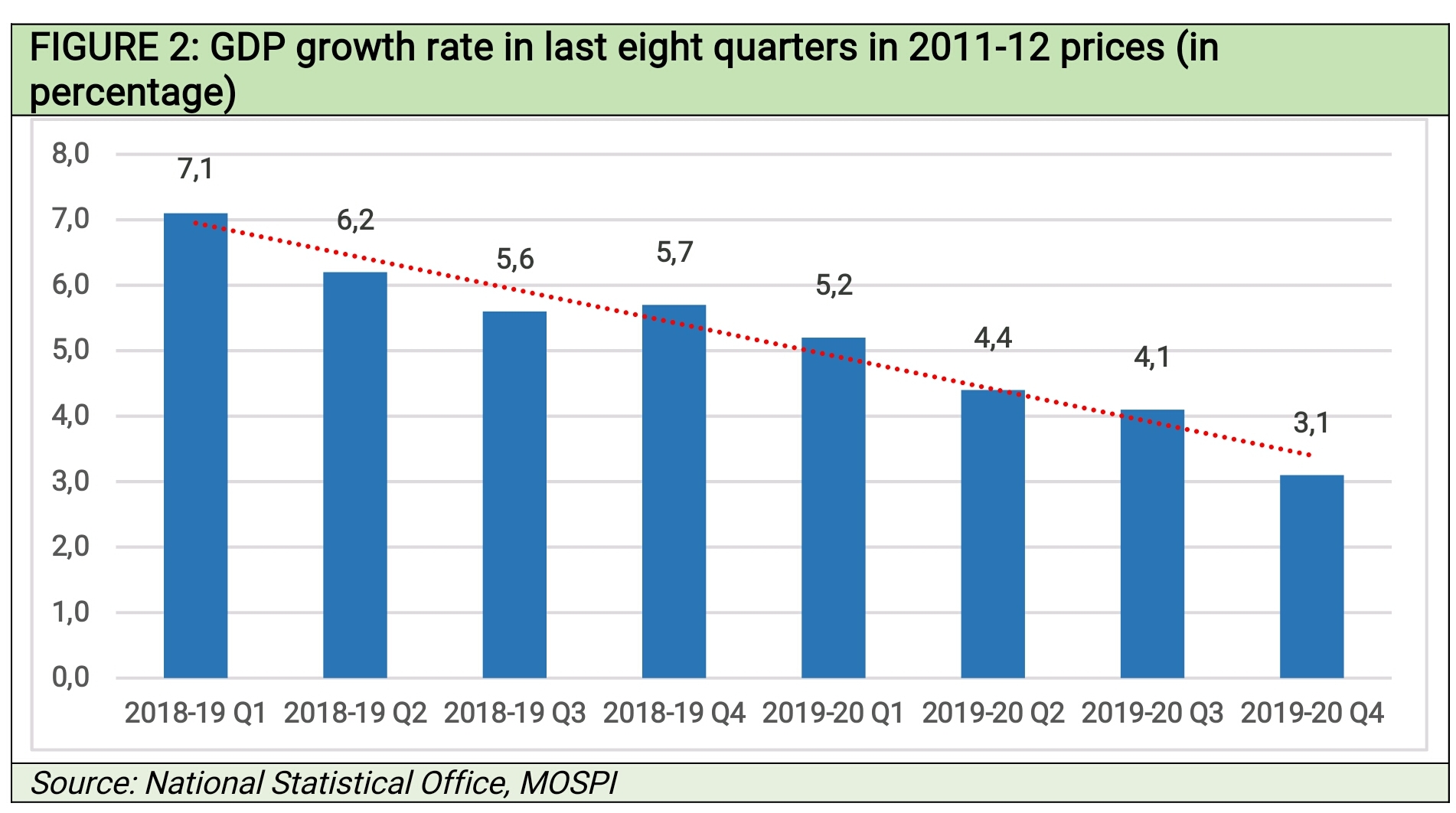

When GDP estimates of India for the fourth quarter (January-March 2020) of the fiscal year 2019-20 were announced on 29th May, the figures belied the hopes generated by IMF projections. Quarter-to-quarter GDP growth rate fell sharply by 3.1%. In the month of March, the national lockdown to stop the spread of pandemic halted economy for around a week, while January and February experienced business as usual. So, 11 weeks of pre-COVID activity failing to prevent the downward slide in GDP growth rates is not an encouraging sign for the future.

Even this quarterly 3.1% growth figure is not above questions. Former Chief Statistician of India suspects this growth rate to be an overestimation. Before the national lockdown was imposed, various affected states (India has 28 states and 9 union territories) went into lockdown –disrupting sectors like tourism and hospitality. Therefore, actual loss maybe significantly higher than the estimated output loss. Because of the Covid-19 disruption, most companies could not submit their quarterly financial returns, and the government may have overestimated production by simply extrapolating previous three quarters’ production figures in the fourth. Moreover, since the unveiling of the new methodology of estimating GDP in 2015, Indian growth rates have been consistently questioned.

Even if one accepts the official GDP growth figures without any doubt, the fact remains that Indian GDP growth rates are steadily declining in the last eight quarters (Figure 2). An economy in prolonged slowdown, even before the pandemic started, is very unlikely to clock a positive growth rate in the next fiscal quarter.

Indian credit rating and consultancy agency CRISIL, towards the end of May, came up with a more realistic GDP projection for the fiscal year 2020-21. It predicts an impending recession – fourth since independence, first since the Indian economy opened up in 1991, and most likely the worst till date. CRISIL Report makes these projections after considering extended national lockdown, rising economic costs, and the feeble economic package by the central government with little fiscal stimulus in it.

Based on these actual happenings, the report has estimated a 25% contraction in the first quarter (April-June, 2020), and an overall recession of 5% in the fiscal year 2020-21. A normal monsoon season (Indian agriculture is rain dependent)is assumed by CRISIL in its projection for the year. The agriculture sector is predicted to grow by 2.5%, but the non-agriculture sector is likely to shrink by 6.3%. Assuming the projection of agriculture growth coincides with future reality, the sector’s 15% share in GDP does not bring much relief to the economy.

The CRISIL report does not consider the following risks: a global meltdown, possibility of a second wave of COVID-19 spread in this calendar year, a bad monsoon and then possible food inflation.

National lockdown in four consecutive phases is already having a negative multiplier effect on the economy. Continuing partial restrictions in most of the geography in India will erode buffer stocks, and keep disrupting supply chains. Frequent disruptions will make achieving economic recovery much longer than expected.

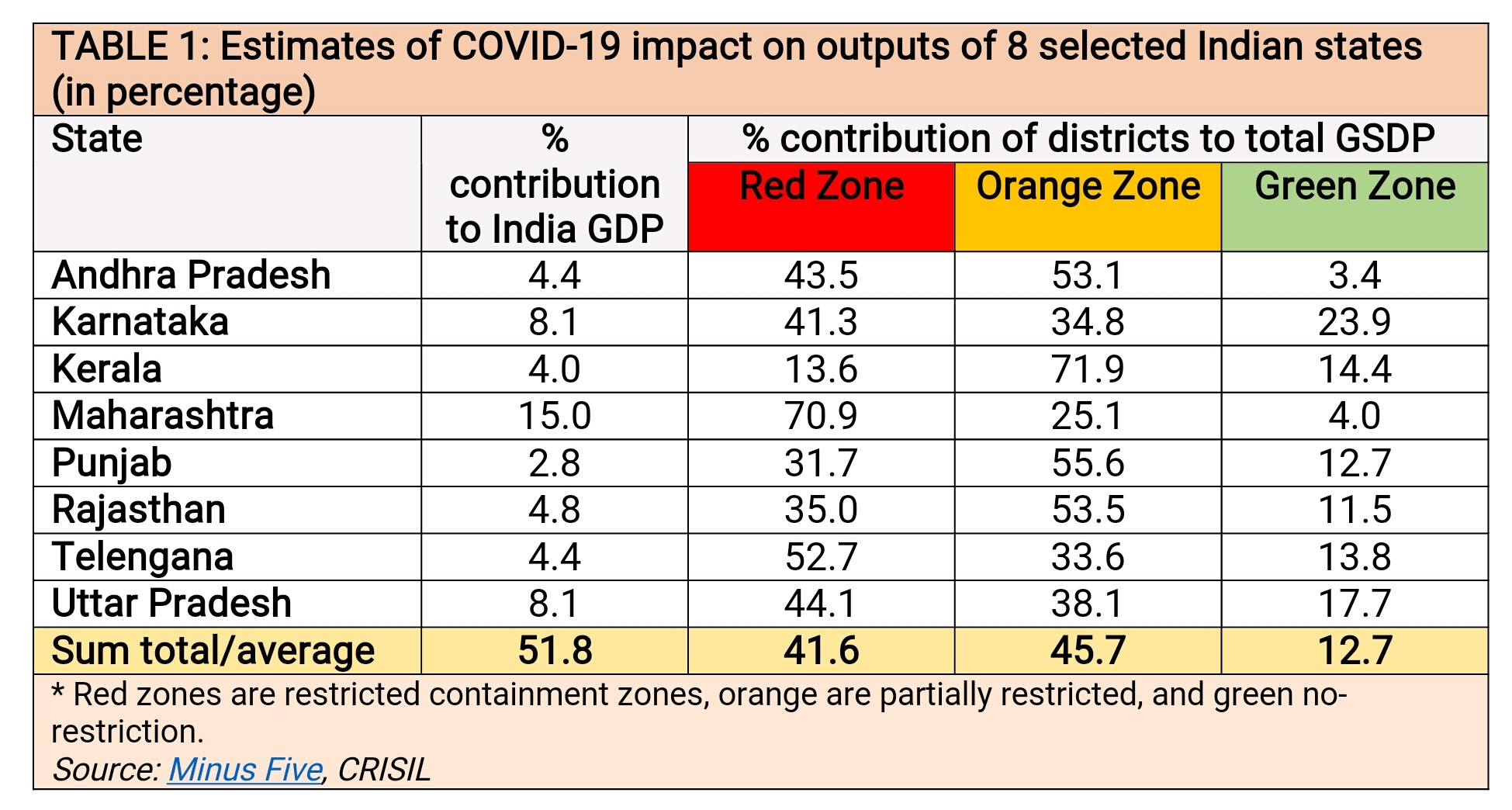

Because district-level (smallest administrative unit in India) GDP data is not available for all states in India, the CRISIL Report took a sample of eight states which contribute around 52% in Indian GDP. The country is now divided into three zones – red being the strictest containment zones, orange partially restricted, and green being the no-restriction zones. On an average, the red zones are seen to be contributing around 42% of GSDP (gross state domestic product), orange zones around 46%, and green zones (where activities are allowed close to normal) contribute about 12% to GSDP (Table 1) in these states.

Thus, even if the national lockdown is lifted to a certain extent, the disruption in important regional and economic pockets will continue. This is quite indicative for the COVID-19 economic impact on India in coming months. Under these circumstances a small positive growth rate in GDP, as suggested by the IMF, looks extremely improbable.

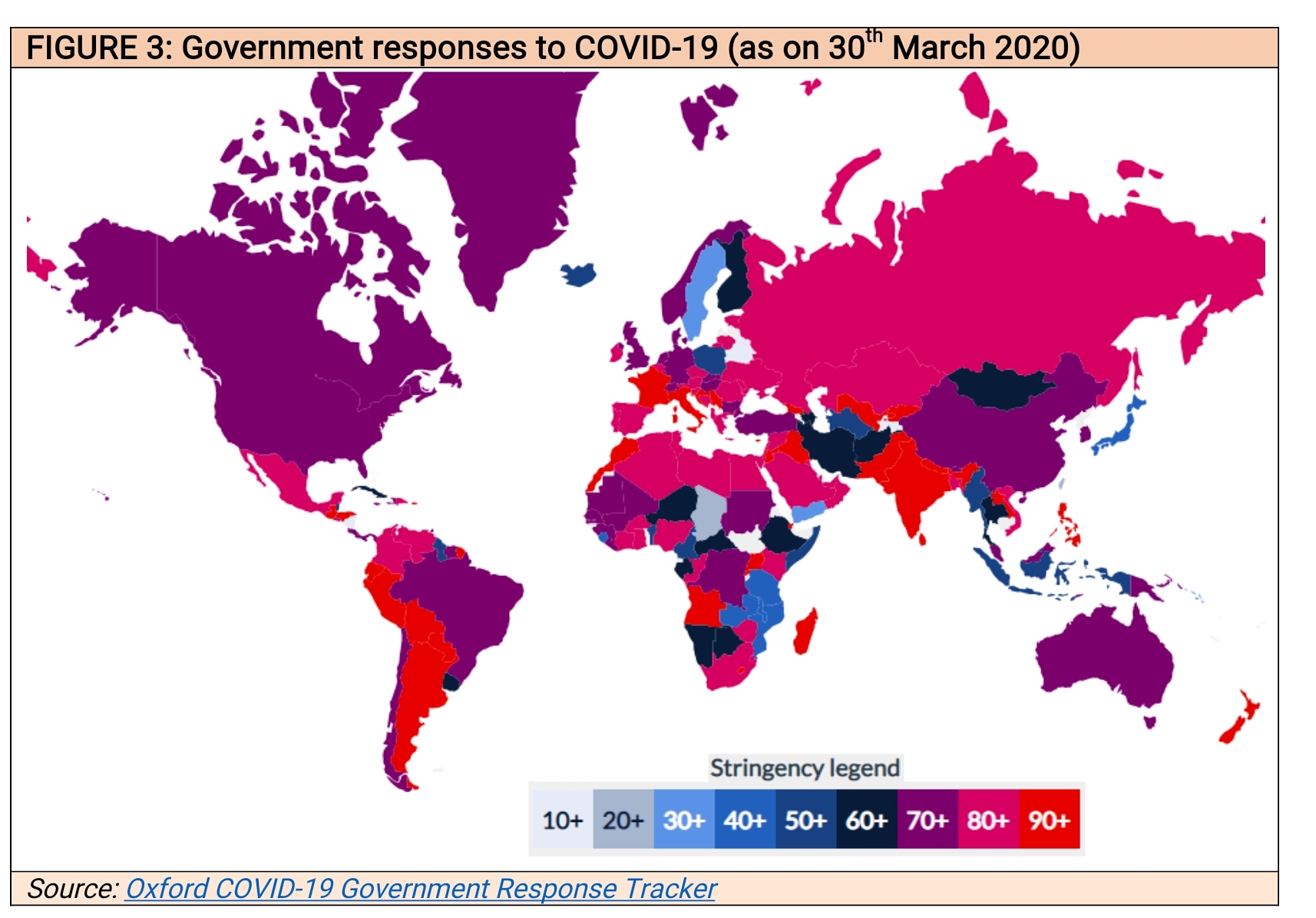

In March, when the Indian lockdown was imposed, it was the third most stringent government response in the entire world, after Peru and France (Figure 3). By that time China started easing restrictions, though it has undertaken stricter restriction again by the end of May in the wake of new recurring spread. Similar eventuality in India cannot be ruled out.

India imposed the lockdown very early, which was then seen as a prudent step. However, the stringent lockdown was not adequately followed up by other required measures of containment like rapidly testing, identifying clusters, augmenting health infrastructure and so on. India’s economic relief package contains a fiscal stimulus of around 1% of GDP, which is not seen as helpful to the larger cause of revival and recovery. In contrast, the fiscal stimulus packages of Japan, the USA and Canada are around 21%, 11% and 10% of their GDPs, respectively.

As a result of the abrupt lockdown, millions of migrant workers were stranded away from their homes. Many of them lost jobs, livelihood, and even shelter. The Indian economy predominantly runs on informal workers with them comprising 80% to 90% of the total workforce. Absolute numbers of these workers are in the range between 400 million to 440 million, according to different estimates. In the absence of immediate relief measures, a majority of these informal workers have gone back to their homes. Given the uncertainties about the spread and containment of Covid-19, they are unlikely to come back to Industrial India very soon. Thus, the cheap labour advantage will be missing for some time and the Indian economy may have to pay a heavy price.